If you’re like me and don’t know much about Artsakh, you might be pleasantly surprised to learn that it’s covered in mountains. If you’re like a certain anonymous dad who I won’t name here, you might sass your daughter on the phone when she exclaims, “I didn’t realize there were so many mountains there!” by responding, “Well, you know, they do call it mountainous Karabakh for a reason.” Not that that’s a true story or anything because what dad would ever say something so rude?

So yes, “they” (you know, the infamous “they” who always have an opinion on things) do, in fact, call Artsakh “mountainous Karabakh”, and with good reason. I would cite some statistic about that except for the fact that I don’t have one, so you’ll just have to take “their” and my word for it (plus my pictures).

We went on a couple of hikes… well, more like “hikes”, aka leisurely strolls through nature. The first one was through Hunot Gorge. There’s a river that runs through the gorge and is crossed in multiple places by questionable bridges that would have gotten someone sued by now if they were in the States. We were with a huge group of people, so the stroll was definitely not the most adventurous experience of my life, but no complaints from me about getting to hang out by a river in the forest! We made it to a kind-of-sort-of swimming area which I wasn’t totally excited about, so a couple of the other volunteers and I asked for permission to go farther on our own. That ended up being the best decision ever because maybe about 7 minutes of walking later (but it was actual hiking that involved some serious inclines), we found a deep swimming hole that we had all to ourselves! The water was frigid, but one of the guys, Arin, and I decided to go for it anyway.

Oh, that was another awesome thing about the trip to Artsakh. You know how sometimes you meet people who you can tell immediately are soul mate friends? Like you just hit it off and conversation and everything is so easy from the very beginning? Arin and I are definitely soul mate friends. He laughs at all of my terrible jokes and makes similarly terrible jokes that I think are funny. You know you’re soul mate friends when no one else is laughing and you can’t understand why not.

Anyway, our swimming hole was awesome and way better than where everyone else was, and once we were completely numb from the water, we hobbled our way out and back to the group.

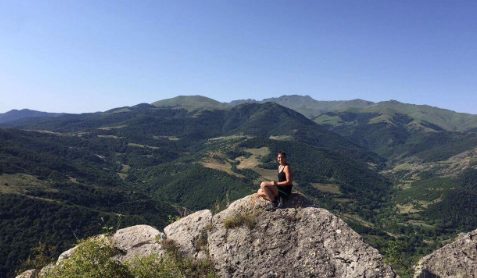

The second hike was right by Shushi. We hiked to Jdrduz (and if it looks to you like that word is impossible to say because how on earth are THAT MANY consonants in a row, welcome to the world of me trying to learn Armenian) which has an awesome view of the valley and also, shocker, has some historical significance. There are ruins of a fortress built into the side of the cliff which was cool but also seemed a little impractical to me. Why not just build it on top? But that aside, looked much more dramatic in that location. And inaccessible.

There’s also a village there, Karintak (which literally means “under the rock” because all Armenian village/monastery/etc names are super creative like that), where a battle took place during the Nagorno-Karabakh War. I mean, yes that’s still going on, but we’re talking back in the days of serious fighting, like the early 1990s. It was an Armenian village that was attacked by Azerbaijan to practice for the attack of Stepanakert. Rather than being an easy victory, the villagers and Armenian forces fought back and managed to squash the attack. History aside, the hike had some great views and was even worth the shadeless trek it took to get there.

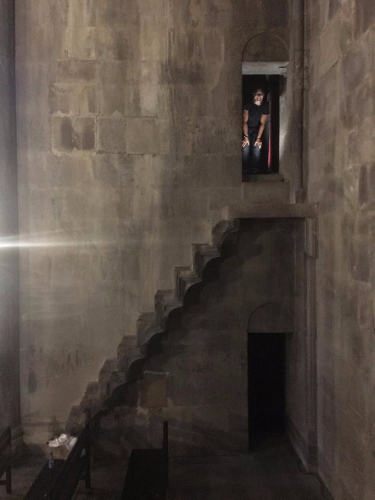

We also visited another monastery, Gandzasar, which had more fantastic mountain views and some awesomely precarious-looking stairs on the inside. I don’t know any crazy stories about this one, so I’ll let the pictures speak for themselves. I’ll just leave you with the fact that the name Gandzasar means “treasure mountain”, and that is just about the coolest name for a monastery in the history of ever.