We left off last time as Mike and I were headed to Teatro Colón, the national opera house, for a tour. In case you didn’t know, I have a theater/opera house obsession… and while I mostly mean the actual buildings, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t also a fan of the shows. My preference is to go to a performance and just creep around admiring the building before and after the show/during intermission, but we were, unfortunately, in town during the performance off-season. So, our only option for seeing the building interior was a tour which, thanks to the fluctuating exchange rate, had a surprise price of $21ish. Eek! That’s a little steep for my preferences, but it was really the only attraction we were paying for, and to me, it was worth it.

We showed up a few minutes early, and I used the time to scope out the other tour attendees. The tour group demographics were approximately 90% people over the age of 60, 9% ages 40-60… and 1% us. I thought it was funny. I think Mike saw it as proof that we should have been anywhere else but there.

All I can say is, those people know what’s up. The tour was fabulous! And the theater, well, there’s a reason why it’s considered one of the best in the world. As usual, though, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s start from the beginning…

The first Teatro Colón, or Columbus Theater (as in, Christopher), was built in 1857 near the Plaza de Mayo. In 1888, the original theater was closed, and a new one was built, finally completed in 1908 during the city’s golden age. Its construction brought the best of the best to Buenos Aires: architects and craftsmen from Italy, marble from Portugal and across Italy, stained glass from Paris, and mosaics from Venice. The builders worked 16-hour days which sounds brutal, and even so, it took nearly 20 years to be completed. The tessellated floors alone took 2 YEARS. Part of the reason for the long timeline was financial, and part was because the two original architects, both Italians, died during the process and had to be replaced. A Belgian architect was brought on to finish the work, and the result is a mix of Italian and French styles. In today’s money, the estimated cost is $300 million USD.

We only visited a few spaces in the HUGE building which is even larger than it appears as two-thirds of it are underground, both beneath the actual building and the surrounding squares. The theater produces everything necessary to put on a show, using its underground workshops for costumes, sets, lighting technology, mechanical special effects, makeup, hairstyling, props, etc. Like I said, EVERYTHING. The underground area also includes rehearsal rooms, offices, and other support spaces. A full-sized practice stage is located beneath the performance stage. Altogether, the theater employs 1,500 people, from performers to technicians to designers and more.

The tour started in the main entry area where the guide explained that builders were brought from Italy specifically for this project. I had just been looking around in awe at the impressive craftsmanship… so that made perfect sense. He said that during the first wave of immigration, 40% of the immigrants were from Italy. These Italian-Argentinians played a huge role in the history of the theater (and the development of the Argentinian “Castellano” dialect).

From there, we headed upstairs where the guide pointed out one of the tricks they used to keep costs down. There’s a lot of marble in the building – yellow from Sienna, red from Verona, and white from Carrara, Italy, and pink from Portugal – but there are also places where stucco was masterfully painted to LOOK like marble. It’s amazingly hard to see the difference, a testament to the skill of the painters, but as soon as you touch the two surfaces, there’s no question. The marble, since it’s actual stone, is much cooler to the touch and has a texture, unlike the stucco which feels smooth. Absolutely amazing, though, that they were able to recreate the appearance of marble so faithfully!

Just above the entrance is the “Golden Hall”. I bet you’ll never guess the reason for the name…

Inspired by the opulence of Versailles (the French palace), the space was originally a social area for the elite. Now, it’s used mostly for lectures, exhibitions, and chamber music concerts, usually with free admission. The gold leaf is partly real. This is kind of funny… starting from 3 meters above ground, it’s real 24-carat gold. Below that, it’s just painted to look like gold leaf. Another cost-saving measure, I presume?

The chandeliers, unlike so many other parts of the building, were actually made in South America. They each weigh half a ton and have 200 lights! I believe it. Could they BE more blinding? The paintings in the room are painted on canvas and attached to the walls/ceiling, and the wood floors (which you can see peeking out past the edges of the carpet) were imported from Croatia.

Recently, a big restoration project was completed, making major structural and technological improvements to the building. Some cosmetic restoration was also completed, like in the Golden Hall where workers tackled 100 years of damage to the room and furniture from smoking and pollution. A few areas were left uncleaned to show the difference, and my gosh, if those spots aren’t convincing enough reasons not to smoke, I don’t know what would be.

And, heading towards the auditorium…

Finally, we got to see the auditorium. It’s the largest in Latin America with a capacity of 2,700 people (300 standing room). Around the main seating area, there are three tiers of boxes and then four more levels of balcony seating. There are also boxes right next to the stage, and looking at them, I wondered why you’d ever want to sit there because the view angle must be terrible. The guide explained that while they do have the worst view of the stage, they are in perfect view of the rest of the audience. Leaders used to sit in these boxes because the most important thing was to be seen, not to actually watch the show. Since those times, the presidential box has been moved to the first level, smack dab in the center with one of the best views in the house.

Again, we learned about how much was happening out of view. The stage area is actually bigger than the auditorium, with prep areas and lifts to the sides and back to store and transport sets and materials as needed to support the performances. It also is 48m tall (155’) which is the entire height of the above-ground building to allow space for the stage lights. The seating area, in contrast, is only 28m tall (90’).

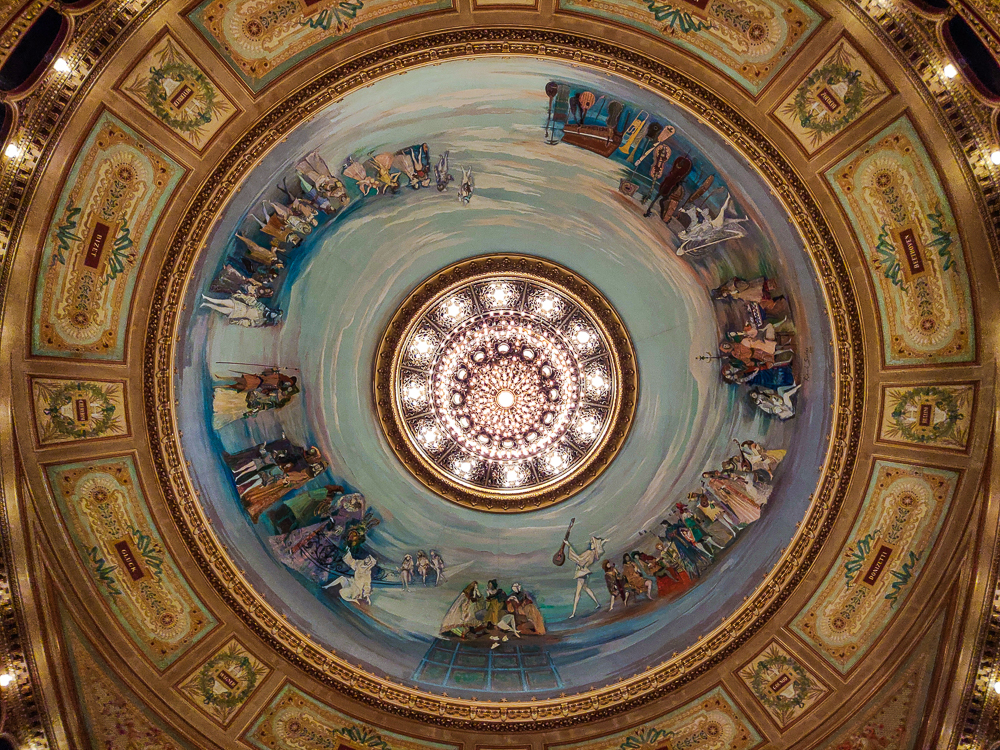

In the auditorium, there are still more hidden surprises. The ceiling sports a painted dome and low-profile chandelier designed to keep from obscuring anyone’s view of the stage. The dome paintings depict life in the opera house. The chandelier has 848 lights (according to the guide. I guess we wouldn’t want to lie and round up to 850) and weighs 1.5 tons. Geez! But the craziest thing is that musicians or singers can actually hide in the ceiling behind the chandelier! There is space for 15 people, and they use it for any sound effects that come from the sky.

Acoustically, the auditorium is ranked in the top 5 best in the world. It was designed with an awareness of acoustic principles, and the horseshoe-shaped space, as well as the material choices, contribute to its success (the lower balconies use softer materials like fabric and wood to absorb sound, while the upper ones are more reflective with harder materials like marble). There’s also a resonance chamber beneath the seats, created by building a second “floor” two meters below the audience. The 84-person orchestra pit can sit at audience level or be lowered two meters to align with the chamber, sending sound through the space and out into the audience via “vents” under the rows of seats.

The theater got a big boost during Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear’s presidency. Remember him? During our mini-tour of Recoleta Cemetery, I briefly mentioned that an Alvear, grandson of General Alvear, served as one of Argentina’s presidents. He also fell in love with a singer, Regina Pacini. Alvear followed her as she performed around Europe, asking her repeatedly to go out with him. Regina refused him time and time again until one night when he bought all of the tickets for her performance, and she went out to dinner with him instead of performing that night.

They fell in love, but she wasn’t willing to give up her career right away. She kept working for five more years, and he followed wherever she went to perform. After the five years, she moved to Argentina, and they got married.

Thanks to Regina’s love of the theater, Alvear paid extra attention to the arts during his time as president. He was responsible for integrating performers into the full-time staff of the theater, whereas it had previously relied on hiring foreign opera, ballet, and choir companies during the season (possible because the summer recess in the northern hemisphere coincided with the winter performance season in the southern). This led to the creation of the Instituto Superior de Arte within the theater, a performance school to train singers and dancers for opera and ballet.

So, you see, the theater really DOES create everything needed for its productions: the sets, the costumes, and even the performers, thanks to the institute. If you’re ever in Buenos Aires and have the chance to go to a show here, GO! And, preferably, bring me with you. Between this and wanting to visit the Museum of Water and Sanitary History, I really don’t think I have any choice. It is imperative that I go back to Argentina! Oh, darn…