Like any “travel day”, the morning of our day-long transit to Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of Machu Picchu Mountain, was a bit hectic. Our friend Amerigo the taxi man (who we met on the way back from Saqsayhuaman) had trouble finding our hotel, but it was okay because he was running EARLY. A Peruvian. Running early. I’d never heard of such a thing.

While Amerigo’s punctuality was surprising, his confusion certainly wasn’t. Our hotel was accessed by walking THROUGH a school. If this sounds like the strangest thing, yes. He called us to say that we gave him the wrong address, that it was a school and he couldn’t find parking because of the morning drop-offs. We told him we’d be right there, grabbed our bags, and weaved our way out to the street, through the crowds of students gathered in the school’s courtyards. Can you imagine something like that in the States? A school with a bunch of strangers walking through at every hour of the day? Yeah, not a chance.

The plan for the day was simple. We left Cusco at 8AM, right on schedule thanks to Amerigo’s early arrival. We had a 3PM train to Aguas Calientes from Ollantaytambo, a town about an hour and a half from Cusco. Along the way, I wanted to stop at two other sites, Moray (an Inca ruin) and the Maras Salt Mines. That gave us seven hours for the drive and sightseeing which seemed like plenty.

As we headed out from Cusco, Amerigo started asking about our plans and if we were staying overnight in Ollantaytambo. I told him no, we were taking the train. He asked if it was the 6:00PM train… nope, the 3:00. He freaked out. He said that we didn’t have enough time, that we should have left hours earlier if we wanted to make the 3PM train. I said that I was pretty sure we were going to be fine. He was adamant, and I started to worry. Was there some road condition or change from my last visit that I didn’t know about? Jocelyn put it into google maps, and the total driving time came back as 2.5ish hours. I didn’t want to insult Amerigo with a “well, google maps says…”, but I was SO confused. And terrified that I had made a huge mistake.

To this point, his driving had been as un-Peruvian as his early arrival… safe and rational. From then, though, it was like he flipped a switch. He morphed into a maniac racecar driver, testing his car’s limits and passing people left and right. A bus tried to run us off the road as we passed it (seriously, what is the deal with these drivers?!?), and we breathed a collective sigh of relief when we didn’t die. I thought Mom was going to hurl. Even though Jocelyn and I were used to Peruvian driving, which is of a similar style even when you’re not in a rush, this was a little scary. I appreciated his determination to get us to our train on time, but it really wasn’t necessary.

Thanks to Amerigo’s breakneck speeds, we got to Moray earlier than expected. I tried to talk to him again after we got out of the car, thinking it would be easier to sort out our misunderstanding face-to-face instead of with Jocelyn and me yelling in Spanish from the back seat. Maybe I was missing something? Or maybe he was planning for more stops than I wanted? Nope. Our conversation resulted in no further clarity. He insisted that we didn’t have enough time and would miss our train. I said I didn’t understand and walked away baffled.

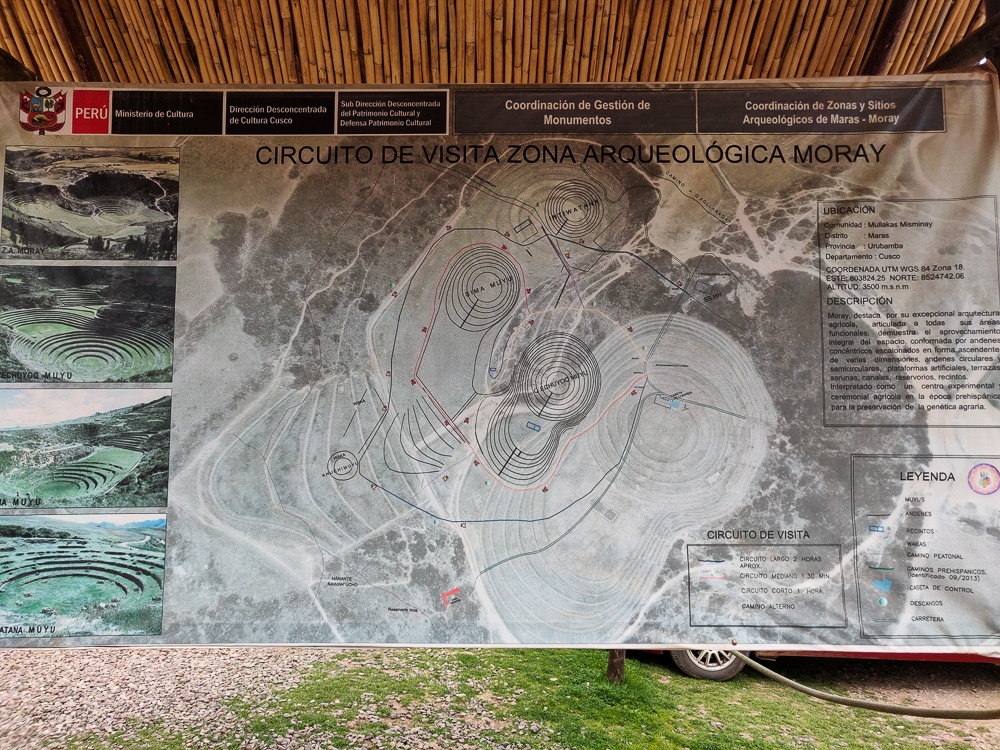

He asked us how long we needed at Moray, and I guessed maybe 20 minutes? 30 minutes? Not too long. He didn’t look like he believed me. There are a few different routes for exploring the ruins: a 2-hour loop that goes around the entire site, a 1.5-hour loop around the main area, or a 1-hour loop to see the highlights. The highlights are sufficient, and looking at the path in real life, I had no idea how it could possibly take an hour. Is that the crawling time? The tortoise time? I don’t know. I usually trust my judgment, but again, I thought I must be missing something since Amerigo didn’t believe me and the sign said it took an hour. We took our time because while I didn’t want to stress him out more, I also didn’t want us to rush through the site for no reason.

Moray is an Inca site unlike any other. The Incas modified the natural topography to create a series of terraced depressions. The leading theory is that this was essentially an agricultural lab where the Incas tested various plants to determine which were best suited to grow in the different parts of the empire. How did this happen all in one site? WELL, this is crazy. Thanks to the depths of the depressions and the orientation in relation to the sun and wind, different climate conditions are created on different terrace levels. The largest depression, for example, is about 100 feet deep, and amazingly, there’s a massive annual temperature difference between the top terrace and the bottom – nearly 27°F (15°C)! Also, soil testing has revealed that different soils were transported from near and far to Moray. With this, the Incas were able to use this one research lab to test the performance of their crops across their diverse empire, from the sea-level desert around Lima to the high-altitude Andes and the tropical Amazon. They determined which crops grew best where and modified them to thrive in various conditions.

If that isn’t impressive enough already, the terraces themselves were engineered to include an irrigation and drainage system. Even today, hundreds of years after they were built, the terraces never flood, no matter how heavily it rains.

We took our time walking the 1-hour loop and were back at Amerigo’s car in 35 minutes… He seemed no less stressed as we headed to our next stop, Maras Salt Mines (the site of my multiple mountain biking wipeouts last time I was in Peru. This visit was slightly more relaxed and involved far less bleeding), but thankfully, there wasn’t much opportunity for maniac driving on the winding back roads we took to get there.

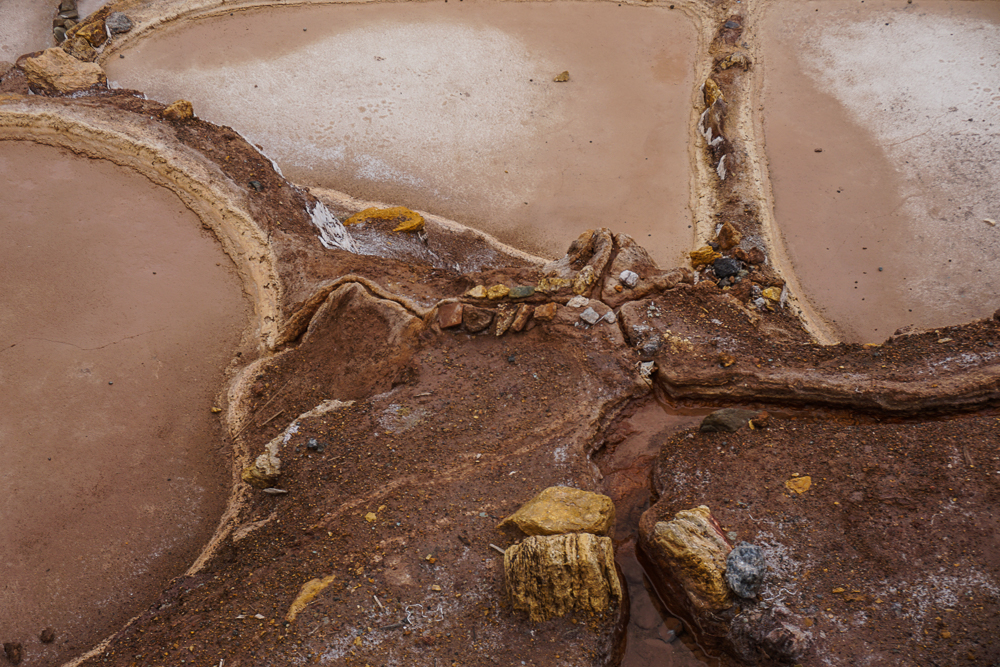

The Maras Salt Mines, unlike the Wieliczka Salt Mines that I visited in Poland, are not underground mines like you’re probably imagining. More accurately, they’re evaporation pools. An underground, salty stream brings water to the site naturally, and it’s distributed among the thousands of man-made, terraced pools by a series of channels. This kind of mastery of water has “Inca” written all over it, but unlike most Inca masterpieces that lie in ruin today, Maras is still being used for its original purpose! Actually, salt production at Maras dates back to the Wari people, a pre-Incan civilization, but the Incas improved and expanded the production area. The setup looks intricate, but the process itself is fairly simple. Salty water fills the shallow pools. The water evaporates. Salt is left behind. This fill/evaporate process is repeated a few times, more salt accumulates, and then, the salt is harvested.

As you might expect, this works better in the dry season when the water evaporates more quickly. This results in higher quality salt, either pink or white in color. In the rainy season, the salt is more likely to have a brown tint to it. The best salt is exported, and the rest is sold in Peru. Even the lowest quality salt can be sold, and while it may not make it to someone’s kitchen table, it is used in industrial processes, agriculture, and raising livestock.

When we’d seen enough, we headed back to the car for the final leg of our journey with Amerigo, from Maras to Ollantaytambo. We met him at the car, and this was the point when he realized that we were not actually going to miss our train. We had more than enough time, in fact, and he resumed driving like a rational human. I breathed a sigh of relief, happy that I wasn’t crazy.

We said our goodbyes to our friend Amerigo as he dropped us off in the main plaza in Ollantaytambo. It was 11:30AM, earlier than expected, thanks to the maniacal speeding. We had more than enough time to eat some lunch and explore the Ollantaytambo ruins before our train left at 3. To be continued…