My first few days in Lebanon were rainy. When I say “rainy”, I’m not talking about just overcast skies and some little showers here and there. I mean that for three straight days, it was like the sky decided to finally unload some serious emotional baggage. I usually don’t believe in umbrellas (don’t bother trying to make sense of me), but no chance was I going out in THAT with just a rain jacket.

We started out by planning “rainy day activities” and ended by defiantly going outside despite the rain. The National Museum of Beirut was stop #1 on the rainy-day Beirut tour, and it was a great way to start off my time in Lebanon! It’s an archaeology museum, and they have a huge variety of artifacts. There are so many different types of things, and they span thousands of years of history. The museum has over 100,000 artifacts, and about 1,300 of them are displayed. If you think that sounds like they’re kind of gypping you, trust me when I say that 1,300 is more than enough. The museum is incredibly well done with enough stuff to make you feel satisfied but not so much that your brain is mush by the time you leave. I was also impressed with their audio guide… they give you an ipad! And you go around the museum scanning barcodes to bring up more information about certain objects. So high tech!

The museum is located right along the road that served as the separating line between the east and west sides of Beirut during the civil war. That meant that there was no chance of the building making it through the war unharmed, so the curator of the museum at the time undertook measures to protect the collection. Some artifacts were relocated to other parts of the country, and other small objects were hidden in the basement. Those storerooms were walled in so that no one even knew they existed, aside from the very few who were involved with the installation. Larger, unmovable objects, such as the mosaics set into the floor and large statues, were encased in wood and concrete and left in place.

The war lasted longer than expected, so despite these protection measures, the collection still suffered greatly. The artifacts hidden in the basement storerooms were in an uncontrolled environment for 15 years. Flooding in the museum led to high humidity levels (around 95%). A fire caused by shelling resulted in the destruction of museum records and artifacts. Large objects suffered damage from the salt in the concrete and the lack of ventilation in their emergency casings. Looting scattered the collection across the world. The building itself was covered in shell and bullet holes and graffiti.

It took 21 years after restoration began for the entire museum to open again. The building needed a serious overhaul, and the collection had to be inventoried and restored. In 1999, four years after restoration efforts began, the museum permanently reopened, but the final floor wasn’t completed until October 2016. The museum is STILL working to track down artifacts that were stolen and sold during the war.

I was lucky that the basement was open by the time I visited. It included some of the coolest stuff in the whole museum… there were three naturally mummified people who were found in a cave, a huge collection of anthropoid sarcophagi, and a 2nd-century frescoed tomb that was relocated from Tyre. I don’t have pictures of the people because it seemed disrespectful or of the tomb because photography isn’t allowed, so I guess you just need to visit Lebanon if you want to see them…

I checked out the National Museum solo, but Badveli and Maria joined me for the next museum on the list, the Nicolas Sursock Museum. During his life, Sursock was an art collector, and his will left his house to the city of Beirut to be converted into an art museum. I’ll be honest, 90% of the reason I wanted to go was just to see the house. It’s a modern/contemporary art museum, and we all know the complicated relationship I have with modern art. I figured that no matter what the art was like, the building would be worth the trip. Badveli was interested in checking out these 19th-century pictures they have of the ruins in Baalbeck, so we made it a family trip!

The house was built in 1912 and is a cool mix of architectural styles, including some elements inspired by Venetian and Ottoman architecture. It also has a bunch of stained glass which basically guarantees that I’m going to like it. The museum first opened with the house kept in its original condition, and exhibitions were shown in the many rooms of the mansion. Eventually, a project was undertaken to reconfigure some of the rooms into more traditional gallery spaces. Recently, a much larger project was completed that added four underground floors beneath the house and garden. I can only imagine how fun that construction process must have been, figuring out how to levitate a mansion while constructing another building underneath it.

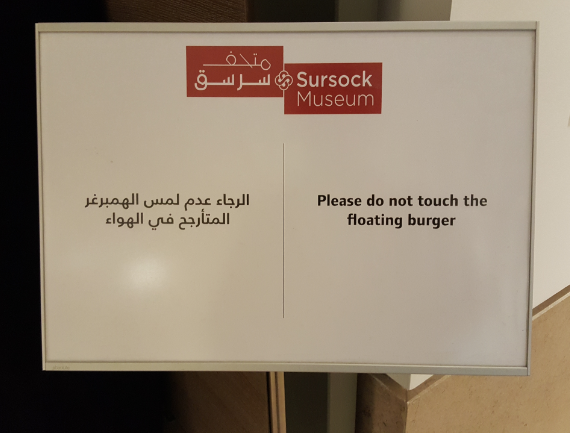

For the most part, the exhibitions were about what I expected… weird. There were a few cool pieces, but it was largely baffling, as is the way with modern art. Don’t get me wrong, I have no issues with weird. I love weird things! But the weirdness of most modern art is a type that must be incompatible with my personal brand of weird. There was one thing though… as we were leaving, we walked past a curtained doorway marked with a sign saying, “Please do not touch the floating burger.” I was intrigued. Burger like hamburger? Why was it floating? What about it made touching it so tempting that they explicitly had to tell people not to? I peeked my head inside, and somehow what I saw was simultaneously exactly what I expected and the last thing that I expected. It was a floating burger. The room was completely dark, a blacker darkness than any I’d ever experienced. The only light shone directly onto a floating hamburger. It was like a beacon, calling you towards it. The burger practically screamed, “TOUCH ME!” I’m not an uncultured scrub… I know that you’re not supposed to touch things at museums, but I’ll be honest. I wanted to touch that burger. HOW DID THEY KNOW? It was like I was hypnotized. There was also a museum staff woman standing by the entrance, probably making sure that the burger was left untouched because I bet she’s felt the same, inexplicable desire that I felt to touch the forbidden burger.

I felt like my faith in modern art was restored… until we left the museum and I read the pamphlet that accompanied the piece. It was something about capitalism and blah blah blah profound symbolism blah blah blah. I immediately forgot what I read because I knew that trying to assign too much meaning would inevitably ruin the whole thing for me. Maybe that’s the problem. I want modern art that has no explanation besides “I made this because I thought it was weird and funny.” Otherwise, it gives me flashbacks to university where we’d make a design that we thought looked cool and then go back later to make up some stupid, symbolic meaning because the project required it. What’s wrong with just saying, “I did this because it looked cool”? To be fair, sometimes the explanations feel legitimate, but most of the time they seem like a bunch of hooey.