The morning after my short day in Guayaquil, I met my aunt, uncle, and cousins at the airport for our flight to San Cristóbal, our first stop in the Galapagos! I was really excited that it worked out for me to travel with their family because while I do love to travel alone, there are some destinations that are even better with travel companions. To me, the Galapagos is one of those (because you need someone to share your disbelief with! It’s a place like none other).

Since the Galapagos Islands are protected, there are lots of hoops to jump through on your way there. We needed to provide all sorts of information about where we were staying and what we were doing, they scanned our luggage to make sure we weren’t bringing any organic materials with us (because non-native seeds and such can really mess things up), and when that whole process was finished, we were off!

No trip is without its drama, and this time, there was some seat assignment debacle happening. I don’t know exactly what it was all about, but I stepped onto the plane and immediately regretted it. Chaos. People were standing in the aisle and yelling at the flight attendants who were frantically looking at papers and passing them back and forth and yelling across the plane. I managed to scoot past the mess and into my seat, but there was still no resolution in sight. The departure time came and went. Tensions were rising. Finally, a man a few rows in front of me stood up and said, “Okay, so whatever happened to mess this up, it doesn’t matter anymore. The flight is only 2 hours long. Can we all just agree to sit in whatever seats are available so that we can get out of here?” A voice of reason. The plane breathed a collective sigh of relief. The problem passengers sat down. We took off. That man was a hero.

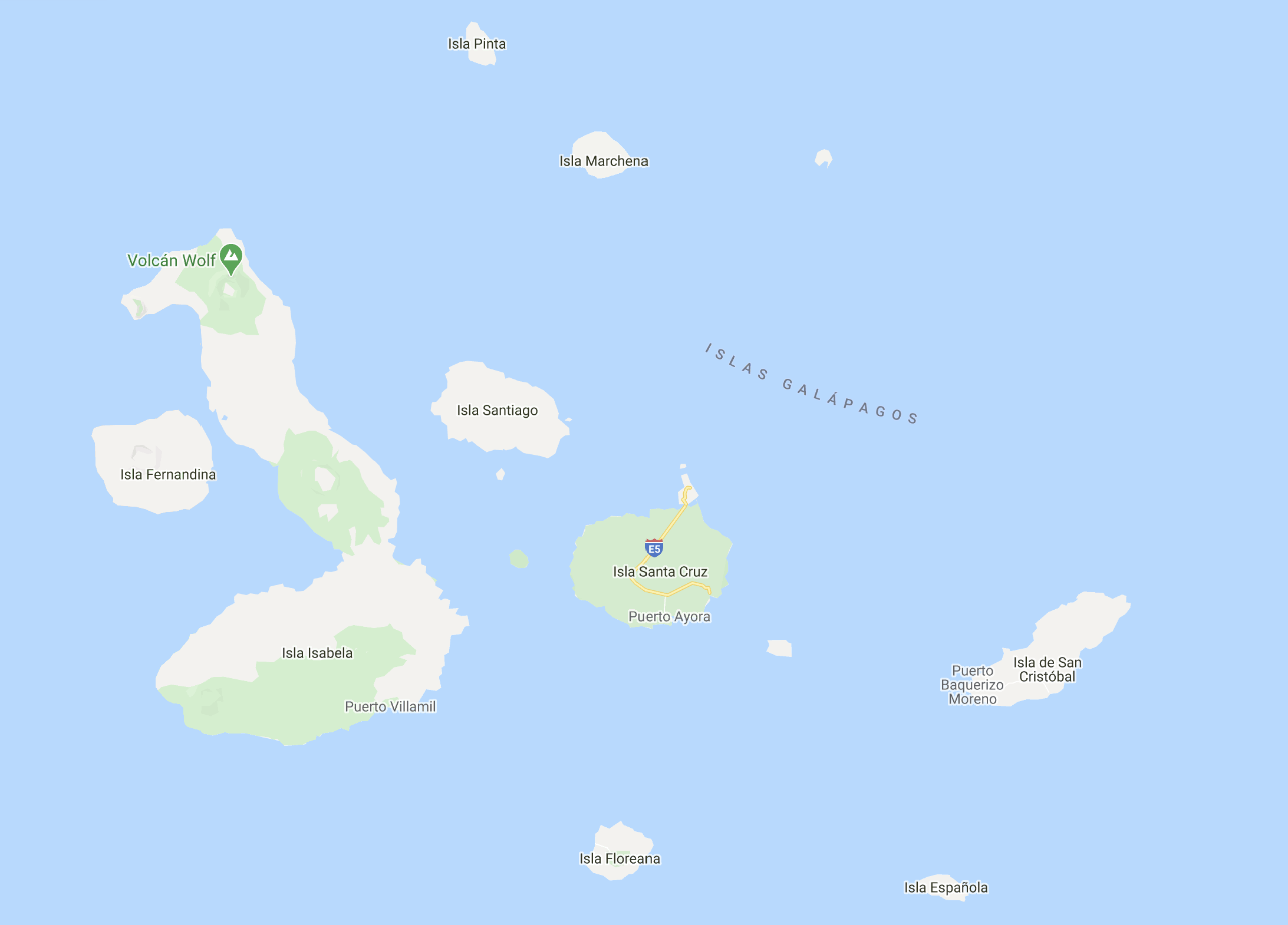

Now that we’re airborne, let’s get some Galapagos backstory. The Galapagos Islands are a volcanically formed archipelago in the Pacific Ocean, straddling the equator about 560 miles (900km) west of Ecuador. There’s a hot spot beneath the earth’s crust, and sometimes, an eruption pierces the crust and sends out a flood of lava that accumulates and cools into an island. Since the earth’s crust is made of tectonic plates, giant areas of crust that are constantly moving, these newly formed islands slowly move away from their source hot spot which remains stationary. The Galapagos are on the Nazca Plate which is moving east towards South America at a rate of about ~1.2”/year (3cm). That may seem slow, but over 50 years, that’s nearly 5 feet (1.5m)! Over millions of years, a group of islands is formed. The oldest Galapagos Islands are on the eastern side, estimated to be 3 million years old. The newer ones to the west are young… more like 50,000 years.

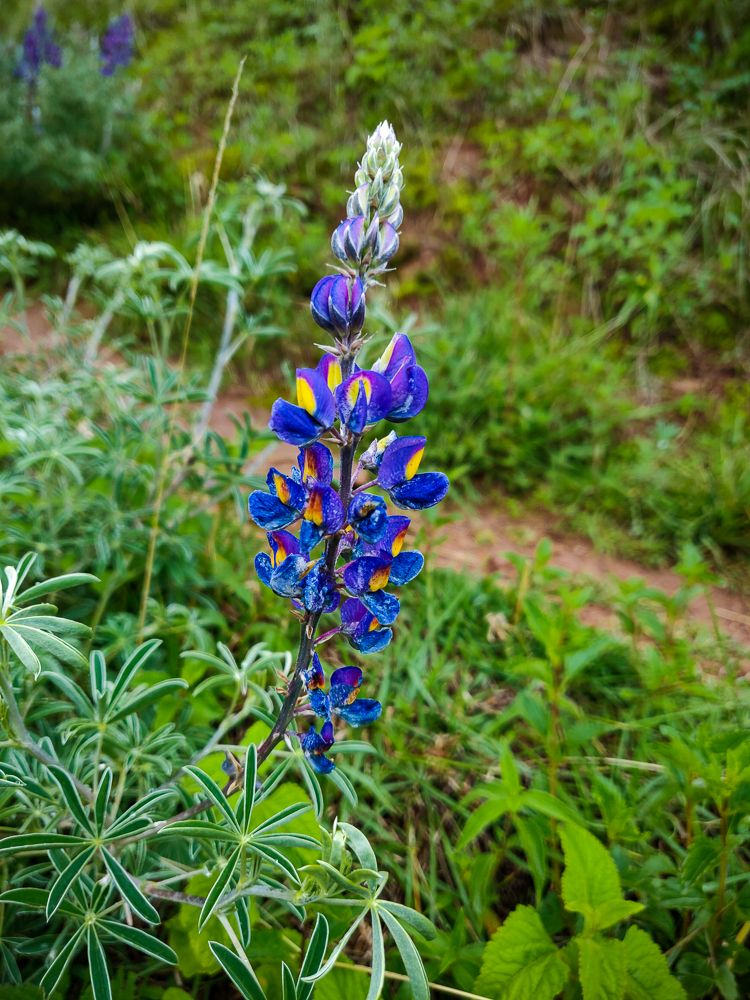

The new islands, as nothing more than mountains of cooled lava, are completely devoid of life and rather inhospitable places. Slowly “pioneer species” make their way there, starting with things like cacti and lichens (fungus algae) that don’t need much to survive. Their seeds come to the islands via winds or tides, a few eventually land in places where they manage to germinate and grow, and slowly, they spread. Saltwater-resistant coastal plants, like mangroves, have a better shot than those requiring fresh water.

This is a good place to explain that one of the reasons why the Galapagos are so unique is because of their location. There are three different currents that converge on the islands: the warm Panama Current from the northeast, the cold Humboldt Current from the southeast, and the Cromwell Current, an upswell current from the west which brings cold water from the ocean depths. In essence, all ocean roads lead to the Galapagos, making them an incredible site for marine diversity, including marine mammals that also spend time on land, like penguins and sea lions.

Okay, now we have some basic plant life and marine life… so how did the land animals arrive? Vegetation rafts (floating masses of vegetation) and other large, floating objects like tree trunks sometimes carry animals as well as plants. From the continent, in favorable conditions, it takes about two weeks to float out to the islands which means that any animal capable of surviving two weeks without freshwater and in the hot sun had a chance to make the Galapagos home. Not surprisingly, this mostly limited the land-dwellers to reptiles, mainly tortoises and land iguanas, that thrived in the absence of predators and competitors.

Finally, the easiest path was taken by sea birds who simply flew to the islands. Many species nest on the various islands, probably attracted in part by the lack of major predators, making the Galapagos an especially famous destination for birders.

Everything that came to the Galapagos had to either quickly adapt to the environment or perish, and the plants and animals that live there today sometimes look very different from their mainland ancestors. One famous example is the Galapagos finches. The thirteen species of finch are differentiated by their beak shapes, each best suited to accessing a particular food source. Charles Darwin visited the Galapagos, and his observations of the finches helped to form his theory of evolution.

The islands have two seasons: hot and garúa (drizzle). Hot is from December-May when the warm NE winds are strongest, and rainfall is abundant. Garúa is June-November when the SE and W winds are strongest. Temperatures are cooler with a persistent garúa.

In the lowlands of the islands, the climate is arid. Some of the larger islands have highland areas as well. Their climates transition from arid lowlands around the coast to almost rainforest-like vegetation (and weather!) in the highlands toward the center. It’s very strange. You can have a bright, sunny day on the coast, but a rainy day is just a quick drive into the highlands away.

Okay, now I’m going to zoom through the human history of the islands because it’s far less interesting and mostly involves lots of bad decisions, people dying, and destruction and exploitation of the islands. Some evidence has been found to suggest that pre-colonial people made it to the islands, likely on large rafts that were driven by the winds and currents. The first written account of their existence is from 1535 by a Spanish missionary named Fray Tomás. A few days after his ship’s departure from Panama, the wind disappeared, and they were left to the mercy of the currents. By the time the ship reached the islands, its passengers were in desperate need of water. It took three days and two islands before they found freshwater pools which they used to refill their stores before heading back to the mainland. Fray Tomás wrote of “sea lions and turtles and tortoises so large that each could carry a man on top of itself, and many iguanas that are like serpents” and said that there were “many birds like those from Spain, but so silly that they didn’t know how to flee, and many were caught by hand”.

About a century later, pirates moved in, using the islands as a refuge and hiding place after attacking Spanish ships. The Spanish then took an interest in the islands, gathering as much information about them as possible to try to stop the pirates. The 1800s brought whalers who hunted the whale-rich waters, killed fur seals for their pelts, and took/killed tortoises for their oil which was used in lamps. This also was the beginning of the introduction of non-native species, a huge issue for the Galapagos wildlife that persists to this day as they threaten the native species by eating their food, eggs, etc. As Fray Tomás noticed with the “silly” birds, their lack of exposure to humans kept them from recognizing the risk they posed. The same is true for other animals. The native species have no time to adapt to them and the new threats they bring.

The early attempts to colonize the islands all ended in disaster. The first was in 1832 and included 80 prisoners who were pardoned in exchange for their work in the colony. Within five years, it failed due to a toxic atmosphere between the colonists and criminals. Criminals continued to be sent to the islands, and in 1839, the new governor transformed the colony into a work camp where overseers dealt harshly with laborers until an 1841 revolt put an end to the whole mess. The next had a better leader, but he was idealistic and was murdered by some of the pardoned convicts he sought to reform… who were then killed by some of the workers who were loyal to the leader. Another failure. In 1879, the next guy produced sugar and treated his laborers (a mix of volunteers and convicts) like prisoners, allowing extreme punishments like whipping, banishment to another island, and death. He was killed by his workers in 1904. In 1925, 2000 Norwegian immigrants tried to set up a community, but the environmental conditions were too much, their business plans failed, and people died, leading most to return to Norway within three years, tired and disillusioned. In the 1940s, a penal colony was set up and became famous for the mistreatment of prisoners and abuse by the guards. This lasted 13 years until an uprising where the convicts took control, stole a yacht, and sailed themselves back to the continent.

Understandably, this run of “bad luck” led many people to believe that the islands were cursed. I think it was nature’s way of saying “keep out” and also “stop sending tyrants and convicts to start colonies because it’s never going to work”.

The Galapagos became a national park in 1959, the same year the penal colony was dissolved. This was a great step, but four centuries of exploitation had taken its toll. The wildlife on and around the islands was greatly depleted both from being killed by humans and by damage caused by the introduction of non-native species. Whaling logs from North American whalers alone list a minimum of 100,000 tortoises taken, meaning multiple times that were probably killed in total. Some tortoise species were lost to extinction, and the ones that are still around have been repopulated with great human effort.

We’ll talk more about some of these things later, but there’s a brief, whirlwind history of the Galapagos!

After we landed on San Cristóbal, we dropped off our bags at our apartment and walked down to the coast to check things out. Within two blocks, we were surrounded by sea lions and iguanas and crabs, and that was the end of our exploring. My uncle explained some camera basics to me, and I was happy as a clam (hehe), trying to take better pictures and figuring out the settings (you’ll see my photos gradually get better from this point on). We did eventually make it about two more blocks to a beach where some sea lions were lounging, and that entertained us until dinnertime.

Everyone was exhausted after that. We had a full-day tour the next day, so I went to bed as soon as I could to prepare for our early start!

Related Posts

Iceland History – visit the world’s largest volcanically formed island, Iceland! While Iceland and the Galapagos were formed the same way, you’ll see what a difference location makes!

Macaw Clay Lick – speaking of birds, head to Peru to admire the colorful macaws of the Amazon Rainforest.

Guayaquil – you know those prisoners who “helped” to colonize the islands? They were sent from the prisons of Guayaquil. Doesn’t that explanation make you want to take a walk around Ecuador’s biggest city? No? Well, you should anyway.