Ready for more walking? How about more rain, some ruins, and a little bit of everything else? I left off my last post at St. George Maronite Cathedral in downtown Beirut. Directly next to the church and Al-Amin Mosque, there’s a large area filled with ruins! At the moment, it doesn’t look like much besides a grass-covered pile of rocks. There are a few columns standing, but besides that, it’s hard to tell what exactly is there. Supposedly though, the ruins date back to the Hellenistic period (around 320BC – 30BC) and have layers from the Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Mamluk, and Ottoman times as well.

The site was discovered during the post-civil war excavations. There’s a procedure to follow when ancient ruins are found during construction: construction halts, the authorities are notified, and archaeological excavations are undertaken until they are considered complete. Then, a decision is made about what will happen, based on the findings and secretly probably the level of influence of the developer. The ruins are either left in place, moved, or demolished to make way for the construction.

These particular ruins have been set aside in the Beirut master plan as an area to be left unbuilt. The intersection of the Roman city’s two major streets was found there, and archaeologists also think that the famous Roman law school was located nearby. They haven’t found the school, but they know it was next to a church whose ruins have been located. There was a competition to decide what to do with the land, and a plan for creating a “Garden of Forgiveness” was selected. The project hopes to be “a step towards social harmony in Beirut by raising awareness about the need to resolve historical grievances”. The plan integrates the ruins and also includes lots of trees and water features and other things that I guess are supposed to suggest peacefulness and harmony. The construction is currently on hold though, so for the time being, the overgrown pile of rocks is here to stay.

There’s ANOTHER St. George church on the other side of the ruins, St. George Greek Orthodox Cathedral. It was originally built in the 1760s, but there had already been churches on the same site for hundreds of years by then. The first known church there was built in the 5th century AD, and that’s the one I mentioned that they know was located next to the Roman law school. That church was destroyed along with the law school in the 6th-century earthquake, and a new church was built in the 12th century. Another earthquake in the 18th century destroyed that one as well, and another new church was built. During the civil war, the church was shelled and left in ruins. Geez. Talk about bad luck.

When they decided to rebuild the church in the 1990s, they used the opportunity that the ruined church presented to conduct some archaeological excavations before reconstruction. Over about a year and a half, archaeologists worked to uncover and decode the layers of history underneath the church. They found the ancient cathedral, plus evidence of other churches built on the site. There are also graves, remains of a paved street, and columns that used to line the colonnaded streets of the Roman city.

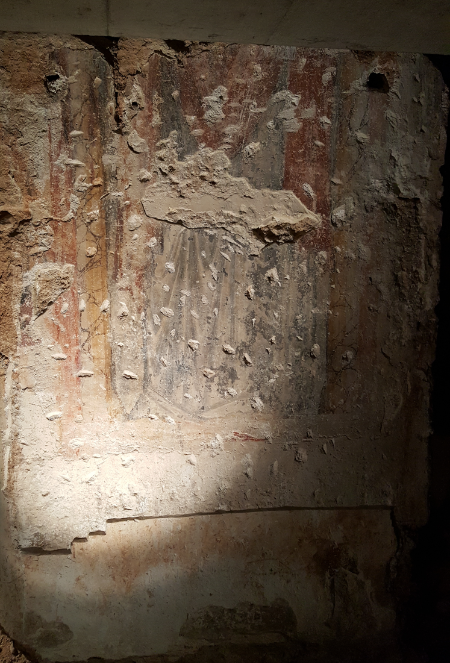

After the excavations were finished, they turned them into a museum and restored the church above. Badveli and went to visit the church first, and it was AWESOME!!!! I love frescoed churches, and literally every surface in this church was covered in frescoes. There were magnificently done, and they actually had them lit so that you could see everything! I wish I’d had all day to scrutinize each fresco, but it would have taken hours to do anything more than quickly glance at them while walking a loop through the church. The frescoes obviously all had to be restored after the war, but a few bullet holes were left as a reminder. I like when they do that… It’s like saying, “We’re rebuilding and moving on because that’s what we have to do, but we also can’t forget about the past or pretend that it never happened.”

From there, we went to the crypt museum to check out the ruins. Badveli had never been before, and I was glad that we were doing something new for him so that the whole day wasn’t just him playing tour guide for a bunch of things he’d already seen a million times (most of the day was that, but thanks to this museum, it wasn’t the WHOLE day).

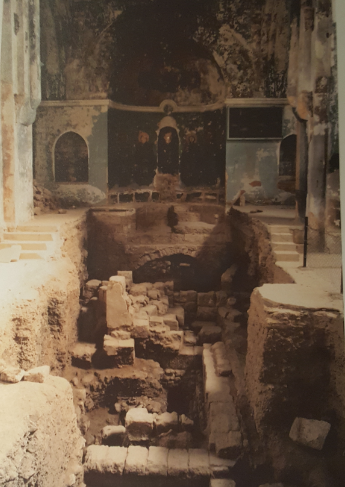

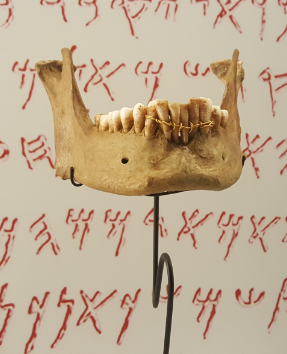

The museum is small, but it’s one of the coolest archaeology museums I’ve ever been to. Since the museum IS the excavation, things are mostly left where they found them. You can see the layers of churches and their different mosaic floors. You can see exactly where graves were found, and a bunch of them still have the skeletons inside. When you first enter, there’s a wall that shows what is basically a vertical timeline of the site. The different material layers in the soil are identified and dated so you can see the various civilizations all stacked on top of one another. The Ottoman layer has a skeleton sticking out, so that’s fun too (eek!). They also have cases with various things in them, but it’s so much cooler knowing that those things were found right next to where they’re now displayed.

It also gives you an idea of how archaeologists piece things together. Since you’re looking at exactly what they were looking at, you can see what columns they used to determine the orientation of the medieval church or the fragment of fresco that was the basis for their assumption that the entire church was painted. The museum has a path for you to follow with numbered stations. At each, you press a button on the information panel, and lights turn on to direct your attention to the places it’s talking about. It was very well done! I felt like I was an archaeologist too, uncovering the secrets of the site as we went from station to station. Maybe I just have an overactive imagination, but it was awesome.

Doesn’t it just look like a cool museum? (I ran around and hit like 5 buttons to turn the lights on for this picture.)

From there, we walked out into the central square of Beirut. There’s a clock tower in the middle (that escaped damage during the civil war because was disassembled and hidden until it was over) and the Parliament building. It’s a bit eerie because the car traffic is incredibly limited there, so it’s practically a ghost town. Fun because you can walk in the middle of the street, but still just a little weird.

Another area of ruins in the city is the Roman baths. They were discovered originally in the late 1960s, were further excavated in the 90s, and are designated as land to remain “unbuilt” in the city. They aren’t the best-preserved baths I’ve ever seen, but they’re definitely still impressive, especially when you think about the fact that they were buried under the city for hundreds of years! The floors are almost completely gone, but they’ve re-set many pieces of the little pillars that held up the floor in the hot room so that the warm air could go underneath. I need to brush up on my Roman bath knowledge again because I didn’t remember too much beyond that, but it was still cool to look at while not knowing anything.

Right near there is the Grand Serail which is the headquarters of the Prime Minister. Badveli said that they can get pretty defensive if you try to take pictures… even if you only want a picture of the Armenian church Surp Nishan that happens to be right next to it. I’m not interested in getting on the wrong side of someone with an assault rifle, so I didn’t try to take one from any closer than from the Roman baths.

From there, we walked over to ANOTHER church, St. Louis Capuchin Cathedral. It was originally built by Capuchin missionaries and is named after the French King Louis IX. By the time we got there, it was getting dark outside which made it extra dark inside. We couldn’t see much of the interior, but luckily, the stained glass windows were still bright! I went back later on during the day, and I got to enjoy the stained glass again and see the pretty paintings on the ceiling above the altar. No matter how many churches I see, I’m still amazed by how each of them has something that makes it different from the rest. I haven’t gotten sick of them yet! That’s saying something, too, because I’ve been to Rome and I’ve been to Armenia, and they both have more than enough churches to keep you busy.

We saw a couple more things after that, but I’m going to save those for later. When we were both about ready to collapse, we decided to walk the 40ish minutes back to the apartment because it was rush hour. That means walking is probably close to as fast as driving, and I wanted to see the nighttime street life anyway. The walk was nice, though it would have been even nicer with functional sidewalks. I know, I know. I expect too much sometimes.

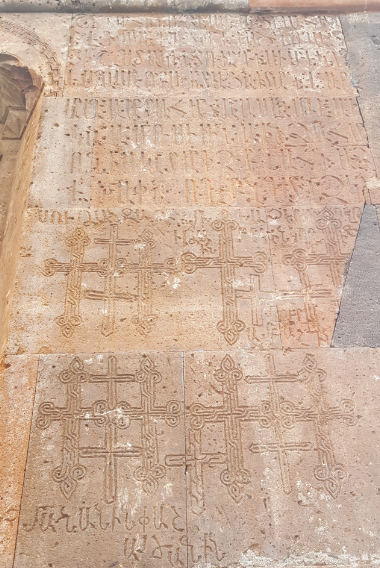

From there, I walked a few blocks to Zoravor Surb Astvatsatsin Church. This place was barely on my radar and ended up being full of surprises! Getting there was the first adventure. It’s hidden in the middle of a bunch of tall apartment buildings. If I hadn’t read about it ahead of time, I would have thought that I was going the wrong way. I was still second guessing my route a bit, and then, out of nowhere, there it was! The church isn’t anything grand or magnificent, but I liked it. There was a service going on inside, and everything about the building felt cozy and homey rather than cold and impersonal like some other churches.

From there, I walked a few blocks to Zoravor Surb Astvatsatsin Church. This place was barely on my radar and ended up being full of surprises! Getting there was the first adventure. It’s hidden in the middle of a bunch of tall apartment buildings. If I hadn’t read about it ahead of time, I would have thought that I was going the wrong way. I was still second guessing my route a bit, and then, out of nowhere, there it was! The church isn’t anything grand or magnificent, but I liked it. There was a service going on inside, and everything about the building felt cozy and homey rather than cold and impersonal like some other churches.

Happy New Year! Շնորհավոր նոր տարի (shnorhavor nor dari)! Wow! Can you believe it? 2018. I’m feeling good about this year based on nothing more than the fact that 8 is my lucky number. This has been my only New Year’s out of the USA, and it was definitely a different kind of experience!

Happy New Year! Շնորհավոր նոր տարի (shnorhavor nor dari)! Wow! Can you believe it? 2018. I’m feeling good about this year based on nothing more than the fact that 8 is my lucky number. This has been my only New Year’s out of the USA, and it was definitely a different kind of experience!