Now that we’ve talked about Inka Pachakuteq and the history of Machu Picchu and have explored the outskirts of the site, it’s finally time to explore the citadel! That’s what they call the main area of buildings onsite even though “citadel” gives more of a fortress vibe, and we’ve already covered the fact that historians think Machu Picchu was most likely a royal estate. That, at least, is the assumption that we’re going to go with as we walk through the site and learn about what the different buildings were potentially used for. Again, everything I say may or may not be true. Thanks to the Incas’ lack of a written language, best guesses are sometimes all that historians can make. So, here are a bunch of best guesses about the ruins at Machu Picchu! Just insert a “maybe” before each statement I make from here on out.

The site can be divided into two main sectors, farming and urban. The farming sector consists of the terraces, many of which are still unexcavated. Vegetation grows quickly in the cloud forest! There are also some buildings around the terraces that may have been used to house farmers, but the majority of the buildings are located in the urban sector/citadel.

After you enter through the ticketing area, you walk up lots of stairs and past lots of farming terraces until you finally get your first glimpse of the urban sector. There are a bunch of different viewpoints from which you can get a low-flying bird’s eye view, and at one of these is the “watchman’s post” or maybe “the hut of the caretaker of the funerary rock” or “call it whatever you want because who knows”. This three-walled structure has a great view of the citadel and the surrounding valley and is one of the few buildings with a restored thatch roof. Remember that this type of roof would have been standard, so based on that alone, the urban sector would have looked very different. Just outside, there’s a large “funerary rock”, carved into an altar and used for embalming and mummification… or maybe used for animal sacrifices. In the nearby field, a number of skeletons were excavated which is part of the reason for the mummy theory. In that case, the hut would have potentially been used in the mummification process as well.

A dry moat separates the outer buildings and farming areas from the urban sector. Through the main gate (that used to have a door with a locking mechanism!), you enter into the upper part of town which contains support buildings like storehouses and public buildings and the remnants of a quarry that likely supplied much of the stone for the buildings. What an exciting welcome to town, right? But it makes sense not to put the really important stuff right next to the city gate, just in case (Lara speculation).

Downhill from these structures is where things start getting interesting. Not surprisingly, the most unique building in the city is the Sun Temple. It has a curved wall with that classic imperial stonework, and it’s built above a giant boulder. The top of that boulder was carved into an altar that was used for animal sacrifices (to read the future in their entrails… ick). This was also where the Inka would come to drink chicha (corn beer) with his “father” the sun, as the Incas believed that the Inka (king) was descended from the sun god, Inti (side note: to keep the royal bloodline pure, each heir had to be a son of the Inka and his sister).

The Incas mummified their dead and treated them a bit like they were still living, so underneath the temple is a “royal tomb”, basically a cave where it is believed that the Inka’s mummy was kept. Even after Inka Pachakuteq died, it is likely that his mummy was brought back to Machu Picchu, kept beneath his father’s temple, and given food and drink (not quite sure about the logistics of that).

Near the sun temple are the royal apartments, aka the residence of the living, pre-mummified Inka. The spring on Machu Picchu Mountain was first directed through the Inka’s apartment so that he could have the freshest possible water, and from there, it flowed through a series of ceremonial fountains. The residence consists of a central patio area surrounded by two large and two small rooms.

Beyond the rock quarry and royal apartments is the main sacred area for the town. A small plaza is bordered by two temples and another room that could have been the priest’s dwelling. You can tell that the temples are important buildings just by looking at their quality stonework.

The sacred spaces continue up “Sacred Hill”. There are more temple-like buildings with high-quality stonework, but again, the exact use of each space isn’t really known. At the top of Sacred Hill is one of the only remaining “Intiwatana”, or “sun fastener”, stones. This carved rock was used during the winter solstice celebration, Inti Raymi, to symbolically tie the sun to the earth. Inti Raymi was a festival to ask Inti not to abandon his people, to move closer instead of farther away. Otherwise, the stone was also used to measure the solar year and keep track of important sun dates like equinoxes and solstices. It was not, however, a sundial or solar clock. The Incas didn’t have clocks as they didn’t measure days in hours and minutes. This hill was also the priest’s pulpit. He could stand high above the main plaza and address the people gathered below.

Across the lawn, right in front of Huayna Picchu, is a “Sacred Rock”. It’s clearly important because a stone pedestal was built around it (it’s a natural projection of the mountain), but what were people worshipping there? It supposedly could look like a puma or a guinea pig, but personally, I don’t see it. Another possibility is that it was simply a representation of a sacred mountain peak. Mountains were believed to have spirits that were considered protectors of the people. I’m going to go with that because I can definitely see “mountain” in this rock.

Finally, moving back towards the main gate but on the other side of the main plaza, there are TONS of buildings. These were apartments for support staff, storehouses, and other utility spaces. There are various interesting features sprinkled throughout these rooms, including these two “water mirrors”. Some guess that they were used to reflect the night sky and study the stars, but that seems silly because why look down at a reflection when you could look up at the real thing? Oh well, at this point, what’s one more unsolved mystery?

On the way out, you walk through one of my favorite parts of town. I don’t know what it was used for… maybe just more support buildings? But the reason I love it is because there are large boulders all over the place, and the buildings are built right into/onto/around them. It’s so cool! There’s one in particular that’s very important, the Temple of the Condor. There’s a huge rock at the center that somehow looks like a landing condor? Condors, pumas, and snakes were sacred animals for the Incas, so it was likely an important religious space.

This is what happens when you do most of your learning about a site AFTER you visit. To be fair, though, it’s very hard to understand what anything is talking about until you’ve been there. I guess that’s one argument for taking a tour, but even so, I think I still prefer exploring on my own.

By the time we were about halfway through the citadel, we were all more than ready to call it a day. Mom and Dad actually said before we even entered the town that they felt like they’d already seen enough. I insisted that we walk through, but I understood their exhaustion. We had already done a lot of walking! We walked through the exit gates EIGHT hours after we walked in. Eight. Hours. But we did it! We survived! And we did/saw everything we wanted to do/see which is VERY impressive.

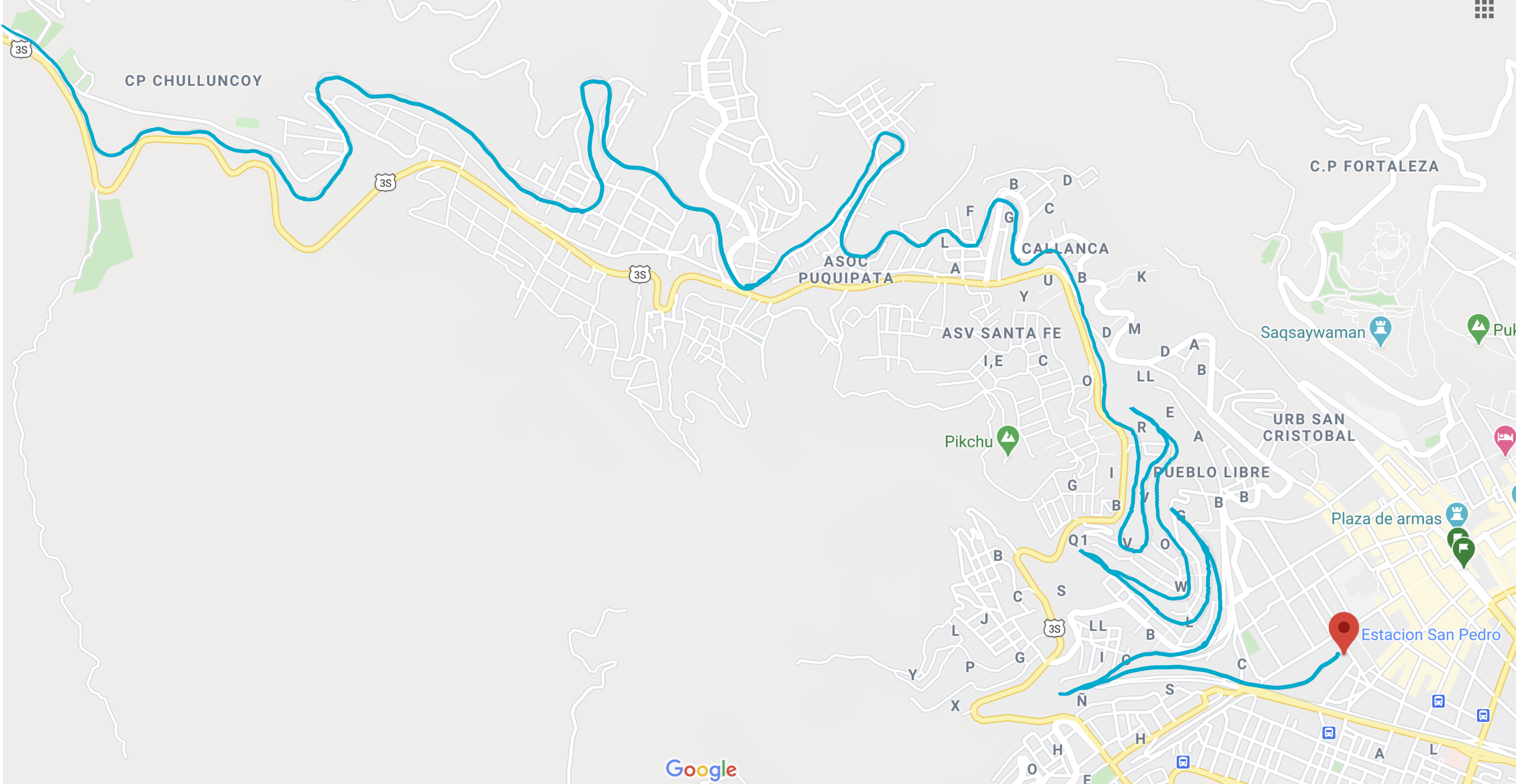

We took the bus back to town and then mostly hung out in our hotel until it was time to head to the train station for our ride back to Cusco. We were taking a train that went all the way back to the city, rather than the other option of having to transfer to a car in Ollantaytambo. Good in theory, but I probably should have looked more closely at the schedule. It’s insane. The train from Machu Picchu to Ollantaytambo takes about 1:45. To drive to Cusco from there would take about 2 hours. The train, on the other hand, took nearly 3 HOURS. How? Well, please direct your attention to the helpful map below. I traced the train tracks in blue.

When we felt like it was time for the ride to be over, we called over the train attendant and grilled him for answers. We could literally SEE Cusco, and he said it was still going to take at least a half-hour to arrive at the station. I was so exhausted that I almost cried. He explained that in order to get down into the valley, the train goes down a series of switchbacks. Switchbacks! For a train! It hits a dead end, they switch the tracks, the back of the train becomes the front, and it continues on until the next dead end. I ranted in delirious Spanish about how silly that was, and he excused himself/escaped at the first opportunity.

Eventually, though, we made it. Everyone was tired of sitting, so we walked the 15 minutes to our hotel and collapsed. Talk about a long day.

Related Posts

Inka Pachakuteq and the History of Machu Picchu – learn about the Inka who built Machu Picchu and how it came to be

Machu Picchu: Inca Bridge and Intipunku (Sun Gate) – take two hikes to interesting features near the citadel

Machu Picchu – come along on my first visit to Machu Picchu, including the hike up Machu Picchu Mountain

Ollantaytambo – explore another royal Inca estate!

Cusco: Q’enko and Saqsayhuaman – admire some impressive Inca stonework at Saqsayhuaman