Today on “Random Places Lara Decided to Visit”, we have one not-random-but-just-happened-to-be-on-the-way place and one google-map-located place.

My plans for the day included visiting the Komitas Pantheon and Yerablur Military Cemetery… because why not just visit a bunch of cemeteries one after the next? Actually though, they’re just kind of in the same direction, and I thought I could visit both on the same day without much trouble.

I took the metro to Sasuntsi David Station on my way to the Pantheon and figured I’d pay a visit to the train station and the famous David of Sassoun statue out front while I was in the area (this is the not-random-but-just-happened-to-be-on-the-way place). Before that, the last time I had been at the train station was when I was moving to Yerevan from Gyumri and was too busy falling asleep/trying to carry my stuff to admire the building. My general thought stream was something like, “hm this is nice. I’m tired. I should come back when it’s light. ZZZzzzZZZzzzZZZ.”

David of Sassoun is a mythological hero of Armenia from a classic folk epic poem. The oral tales about David date back to between the 8th and 10th centuries. They were passed down from generation to generation and were finally recorded for the first time in written form in 1873 by Garegin Srvantsdiants, an Armenian bishop. It took him days to record it as it was narrated to him. In 1903, Hovhannes Tumanian, a famous Armenian poet, created a rhymed version. During the Soviet years, the story was further developed and made into a more coherent work because as a previously oral work, there were well over 100 variations of the story. The entire epic is called “Daredevils of Sassoun”, and it’s like the Armenian Illiad. It is divided into four parts that tell the stories of four generations of a family.

Sasuntsi David appears in the third part of the epic. He is a giant with super strength. He is brave, generous, selfless, peace-loving, honest, upright, and patriotic. He will do anything to protect his land and his people. The overarching theme of the epic is good vs. evil and fighting for justice.

David was the son of a king and queen who previously had no children. They were visited by an angel who told them that they could have a child, but they would die immediately after he was born. They agreed, and so David started his life as an orphan.

He was a very strong boy, and after he grew up, he took his place as defender of the Armenian people. Throughout the epic, he fearlessly defends his people against invaders from Egypt and Persia. In one battle, to avoid shedding the blood of the enemy soldiers, he challenges their leader to a duel and emerges victorious.

The statue was sculpted by Yervand Kochar and was unveiled in 1959. Kochar was an Armenian sculptor and artist who was born in Tbilisi, Georgia, lived in Paris while his career developed, and eventually moved to Soviet Armenia. Sasuntsi David is one of his most famous works, depicting David on his faithful steed and holding his sword of lightning. It’s a pretty… epic… statue (hehe).

The train station is behind the statue, and it was built in 1956. I think the inside is really nice, but there are currently some weird red lines all over the ceiling and walls, and they kind of ruin things. I thought that they were just an addition for the holidays, but they’re still there now, so I’m not quite sure what’s going on.

From there, I walked to the Komitas Pantheon which I’m going to write about separately, and finally, I made my way to Yerablur Military Cemetery. It’s on the outskirts of Yerevan, so I took a marshrutka there, and we wound our way through the surrounding neighborhoods before finally making it to the base of the hill where the cemetery is located. There’s nothing else in the area. It’s just built on top of a hill in the middle of a lowkey neighborhood. If I didn’t know it was there (and wasn’t following along on my phone map), I would have thought I was in the wrong place.

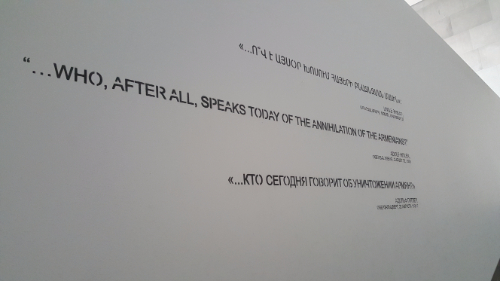

The cemetery was established in 1992 and is for Armenian soldiers who lost their lives during the Nagorno-Karabakh War. There are over 700 people buried there.

I just wanted to go and pay my respects. I knew it wouldn’t be a happy trip, but war isn’t a happy thing. I try not to shield myself from unpleasant things because then you can make yourself forget how unpleasant they are. Then you start to think things like, “Oh, Armenia is in a never-ending war, and that’s just the way things are,” instead of thinking about the fact that war is a horrible thing and it takes the lives of fathers, brothers, sons, and friends. Each number in a death toll statistic was a person, and that person’s death was heartbreaking for a lot of others.

One thing that I noticed very quickly was the general youth of most of the people buried there. As much as I feel like I’m getting old, I’m really not. Meanwhile, I would say that at least half of the people buried there never even made it to my age. The youngest person I saw was 15. A huge number of graves were for 18-22 years olds. At 18, you haven’t even gotten to the best stuff in life. Things only get better from there, and none of those people got to experience that.

Most of the graves are from about 25-30 years ago, but so many had fresh flowers on them. Some of them smelled like freshly burned incense. Thirty years, and those families are still feeling the loss. Everyone else might forget or be able to put the war out of their minds, but they don’t have that luxury. Then, there are the families who have sons there now, the kids doing their mandatory two-year military service. I don’t doubt that those families, those mothers especially, don’t let a single day pass without thinking about the war. It’s not right. Life shouldn’t have to be like that.

From the cemetery, I could see a shiny church that I wanted to visit since the first time its gold roof caught my eye. I thought it didn’t look too far away… so I walked there. Probably not my best call because despite the fact that the distance was quite walkable, it wasn’t terribly pedestrian friendly. Live and learn… and I did live, so now we can all just laugh it off as a funny story that happened in the past and isn’t a big deal because it all turned out okay (Mom – I’m fine.).

On the bright side, the church was very pretty and worth the visit. There was a groundskeeper who came out to see what I was doing, and I was so busy trying to reassure him that I wasn’t up to anything shady that I didn’t even think to ask if he could open the door and show me the inside. I did my best to peek in the windows, and from what I could see, it looked beautiful. I bet he would have let me in, too. Life lessons: you’ll never know the answer unless you ask. And here, the answer is so frequently yes.

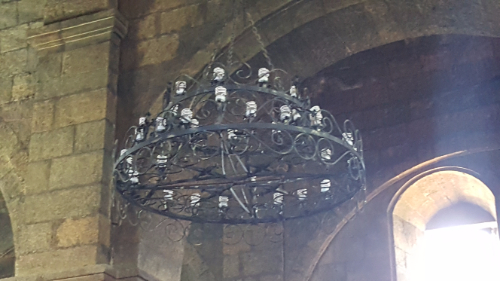

From there, I walked a few blocks to Zoravor Surb Astvatsatsin Church. This place was barely on my radar and ended up being full of surprises! Getting there was the first adventure. It’s hidden in the middle of a bunch of tall apartment buildings. If I hadn’t read about it ahead of time, I would have thought that I was going the wrong way. I was still second guessing my route a bit, and then, out of nowhere, there it was! The church isn’t anything grand or magnificent, but I liked it. There was a service going on inside, and everything about the building felt cozy and homey rather than cold and impersonal like some other churches.

From there, I walked a few blocks to Zoravor Surb Astvatsatsin Church. This place was barely on my radar and ended up being full of surprises! Getting there was the first adventure. It’s hidden in the middle of a bunch of tall apartment buildings. If I hadn’t read about it ahead of time, I would have thought that I was going the wrong way. I was still second guessing my route a bit, and then, out of nowhere, there it was! The church isn’t anything grand or magnificent, but I liked it. There was a service going on inside, and everything about the building felt cozy and homey rather than cold and impersonal like some other churches.