As I explained in my last post, Auschwitz was actually a camp in many parts. The two largest were Auschwitz I which I talked about, and Auschwitz II-Birkenau which is probably the most well-known.

Auschwitz I was built first. It was mostly for political prisoners and some POWs and was a concentration camp. This was where the gas chamber “trial runs” took place, in buildings modified for the purpose of mass murder.

Construction on Auschwitz II-Birkenau started in 1941. The goal was a camp for 200,000 prisoners of war. It was also decided that mass execution facilities would be included, and these were ready by 1942. It became a combination concentration and extermination camp where the majority of concentration camp prisoners died due to starvation, and extermination camp prisoners were killed in gas chambers.

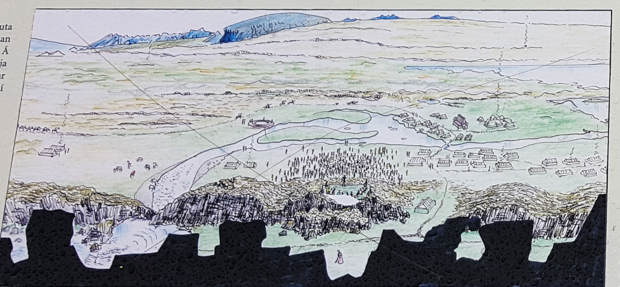

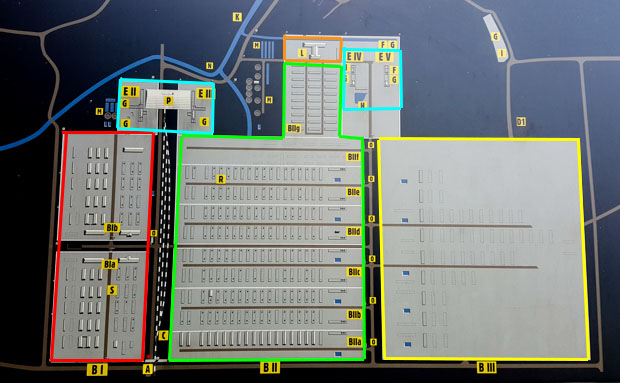

Red – Sector I, built first, brick buildings, primarily barracks

Green – Sector II, wooden barracks divided by row into different “camps” for men, women, Roma families, etc.

Yellow – Sector III, never completed

Blue – locations of the four purpose-built gas chambers

Orange – shower house for concentration camp prisoners

Between red and green is the entrance and the railroad tracks through the camp.

Ten-thousand Soviet POWs were brought to Auschwitz I to construct Birkenau. Through the winter, they worked and walked the 2.5km between the camps. Over 9,000 of them died within 6 months. In total, 300 buildings were constructed at Birkenau, mostly prisoner barracks. The original gas chambers were located in modified farmhouses near the camp, and eventually, four much larger chambers were constructed. The Nazis estimated that 1.6 million people could be killed there each year.

Today, much of Auschwitz II-Birkenau is in ruins. In 1944, when the Soviet army started moving across Poland, the Nazis began trying to cover their tracks at Birkenau. Written records were destroyed, buildings were burned to the ground, and the gas chambers and crematoria were blown up. Most prisoners were transferred to other camps, and the remainder was sent on a death march to the west.

Auschwitz II-Birkenau was liberated by the Soviet army on January 27, 1945. Conservative estimates are that 1.3 million people were imprisoned at the Auschwitz camps, and 1.1 million of them died. Of those prisoners: 1.1 million were Jews; ~150,000 Poles; 23,000 Roma; 15,000 Soviet POWs; and 25,000 prisoners from other ethnic groups. Those numbers don’t add up because everything is estimated. No one knows exactly how many people were killed, and it’s probably more than 1.1 million.

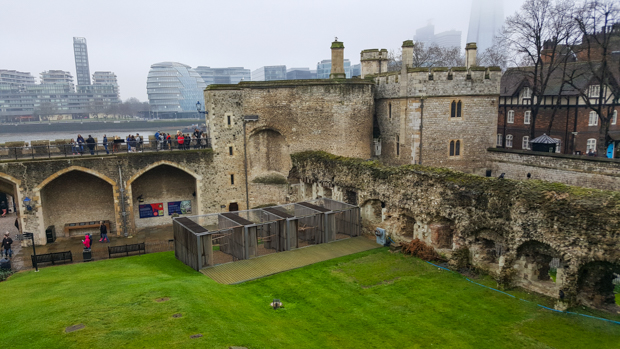

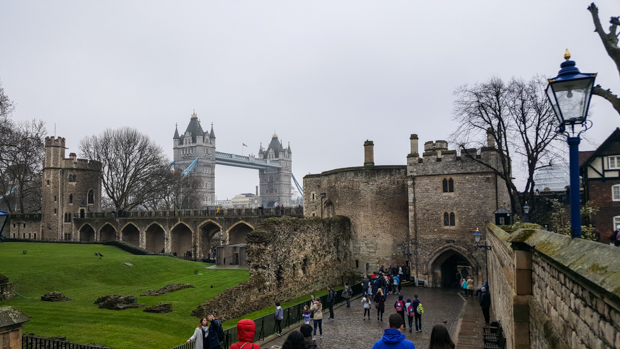

Walking through the entryway into Auschwitz II-Birkenau, my first reaction was, “Wow. This place is huge.” My second reaction was one of recognition. It looks exactly like it does in movies and pictures. I know that’s obvious, but looking at a black and white picture can sometimes feel like fiction. You can separate yourself from it. Standing there, seeing it all in full color, I couldn’t do that anymore.

I had no plan for where to start, so I went in the less-travelled direction, hoping to get away from the crowds. I walked by a row of wooden barracks, the only ones that can be seen today as they were (though much cleaner now) during the camp’s operation. These structures were prefabricated barns, quick and easy to assemble.

The other visitors quickly thinned out as I moved away from the entrance. I spent the rest of my time wandering the grounds with practically no one else around me… I suppose most people simply come in the entrance, walk to the memorial straight ahead, and then turn around and walk right back out. I, on the other hand, wanted to see as much as I could manage.

After passing the first row of wooden barracks, intact buildings were few and far between. Almost more eerie is what remains of the majority of the camp… all of the wooden shells are gone, and only the brick stoves and chimneys remain. Brick chimneys pop up as far as the eye can see. Imagining a building to go with each pair is mind-boggling. Imagining 500 half-starved prisoners to go with each building is painful.

I was already feeling a little uneasy after only walking a few paths. I started feeling better immediately when I spotted a grove of trees ahead. I love forests… they always make me feel at ease. This one was beautiful. Towering trees, sunlight filtering through the branches just right, wildflowers scattered here and there. Again, I had that feeling of “if only things had happened differently, this place would be beautiful.” And then, I came across a sign that reminded me of where I was.

“On their arrival in Auschwitz most Jews were sent by the SS for immediate death in the gas chambers. However, they were often forced to await their turn in this clump of trees if the gas chambers were full at the time.” It was accompanied by a picture of people sitting underneath the trees, waiting for death. Those same trees that I was just admiring. The things those trees have seen, and they keep standing there, still living. I wonder if those people also thought about how pretty the trees looked. Did they know what awaited them? How lucky am I that I can go to these places freely and then leave again? No one is telling me that I can’t, controlling my movements, hating me for no reason.

Beyond the trees, there are fields and a lake marked with signs saying that they’re filled with the ashes of the dead. People. People are in those fields. Their ashes are the ground that the grass grew from. What. If I didn’t know, I could have just walked across them. Walked across these graveyards for literally THOUSANDS. Hundreds of thousands. More than a million people were killed at Auschwitz. 1.1 million people. There are plenty of countries made up of fewer people than that.

“To the memory of the men, women, and children who fell victim to the Nazi genocide.

In this pond lie their ashes.

May their souls rest in peace.”

The thing is, unless you really, really make yourself think about it, unless you stand there and imagine the scared, naked, innocent people in front of you, it’s easy to feel nothing at all. It’s like you’re numb. Your brain doesn’t want to feel the full weight of the truth, so it doesn’t allow you to. Unless you push through your mind’s self-preservation wall, you don’t feel anything. Everything is written so factually that it’s possible to just read it factually. “The gas chambers at Auschwitz were designed to hold 2,000 people at once.” Oh, okay. But then if you stop and think about it. What does 2,000 people look like? My high school had about 1,200. That’s more than 1.5x my high school’s student body. All of those people, gone, dead within 3-15 minutes. All of those people were connected to so many other people. That’s the other thing. When you think about people as numbers, it’s not as meaningful. When you think if it as 2,000 families losing someone so incredibly dear to them, it’s harder. Or when you think about an entire family wiped from the face of the earth. How do you even comprehend that? Sometimes, one person survived from a family. What if that happened to my family, if I was the one person who survived? What if I could never talk to my parents again or see my brothers or nieces or cousins? If I knew that they were all gone forever, and I, for some reason, survived? How do you go on? How do you start over and integrate back into society after years of seeing and experiencing horrors beyond comprehension? I don’t know how I could manage to pick myself up after something like that.

The most disturbing thing is the realization that none of that pain was necessary. Sometimes, people die young. They get sick or get in an accident, and it’s heartbreaking. This though, this wasn’t an accident. It was a complete disregard for human life. Each of those people had a personality. They had dreams and thoughts and talents. They had people they loved, things they enjoyed. They laughed, they cried, they felt. Each person was not a number. They were humans, filled with life and light, and in an instant, they were turned into empty shells. In an instant, their bodies went from being animated and alive to being nothing.

The “sorting area” near the train tracks is another place where all you can do is shake your head because none of it makes sense. This is where people got off a train and were assigned to life or death. All of those precious little children and strong grandparents and loving parents were scrutinized and sorted. Already, they were nothing but bodies. No one cared about their minds or personalities. The question was, is this creature physically capable of labor? They weren’t people; they were tools.

The gas chambers were dynamited, but still, looking at the ruins and knowing what happened in there, how do you begin to make your brain process that? I couldn’t. I tried to imagine the trains coming in. The chaos and disorder as people got off. The confusion, the shouting, the crying. The families trying to make sure everyone was together. Then, the sorting. People getting ripped away from their loved ones. Mothers from fathers from their children. Not knowing what was coming. Being told that you were going to shower. The discomfort of undressing in front of so many other people. Undressing your kids first, the ones too young to help themselves. Then you. Then waiting. Going into the shower room, making sure that your kids were with you. “Stay close, it’s crowded.” And then that’s it. Then there’s a room filled with empty shells of people, and later, there’s only ash, sprinkled in a field. One minute there’s all that life, the next minute there’s an empty field filled with ash. What the heck. What the freaking heck.

Again, I got to the point where I just had to leave. I didn’t want to be there anymore. I didn’t want to see the ruins of the rows and rows of buildings that used to hold PEOPLE. How? That’s the ongoing question in my brain. How could people do this to people?