I left Auschwitz around 4PM and took a bus back to Kraków. I had plans to leave Poland the following day, and I still had one thing I wanted to do – visit the Wieliczka Salt Mines. My original plan was to visit the mines in the morning before leaving town, but that didn’t seem like the most relaxing schedule. I started thinking maybe I should try to make it to the salt mines that day. I’d be back to Kraków by 5:40, it was another 25-minute bus ride to the mines, and the last tour was at 7PM. I hoped the bus would be on time and the tours wouldn’t be sold out (according to the internet, it’s a popular place with limited tickets) and decided it was worth a try, right?

I arrived at the mines at 6:20 and ran to the ticket office to see if there were any more English tour tickets. The woman at the counter printed me a ticket for 6:30! Perfect! Everything was going according to plan. I couldn’t figure out where I was supposed to go to wait… I mean, there was an area with signs for different languages, but no one was standing there which made me second guess it. Since I had no other ideas, I decided to hover around there at 6:30 and hope someone would come to talk to me. A woman asked if I was there for the English tour, I said yes, she took my ticket, and in I went! Inside, there was no one. The woman told me to wait a minute, and she came back with the guide. I was still confused. He said, “I think we have one more person,” and went off to try to find them. When he came back, he said, “Nevermind!” and told me to follow him. What.

Yup, I was the sole member of a group tour. Just me and the guide whose name started with an M and was super Polish and even though he offered like 3 alternatives for what he could be called, I couldn’t handle any of them. Some people might not like being the only one on a tour, but I love it. There’s no struggle to hear the guide, and I can ask every single question that comes into my head without worrying about annoying the other people on the tour. Guides are always more than happy to answer questions.

M was funny (yes, we’re going to call him M). He made corny jokes and laughed at my ridiculous questions, in between his apologies about how his English wasn’t very good. That’s what people always say when they speak perfect English. The first time he said it, I kind of laughed and then protested adamantly when I realized he was serious. I mean, come on. My Polish was so bad that I couldn’t even say his NAME, and he was cracking jokes back and forth with me in English.

The Wieliczka salt deposits are 13 million years old. People began harvesting salt from the area as early as 6000 years ago by collecting surface brine in clay pots, evaporating the water, and using the salt left behind. When the surface water ran out, they started digging wells and found rock salt instead of more water.

The first mining shaft was dug in the 13th century, and tourism to the mine started in the 15th! The early tourists were guests of the king. Mining was dangerous work. The two biggest dangers were cave-ins and methane buildup. This mine never had any cave-ins, and people were sent ahead with torches to burn any methane out of the air. The floors were also very slippery, making it easy for people to slip down the stairs (especially while carrying heavy rock salt).

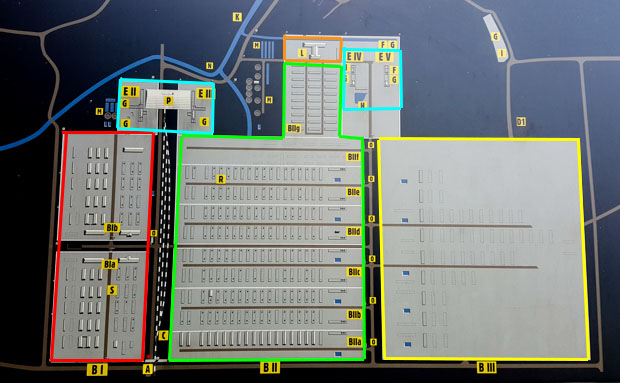

In total, there are about 2,000 chambers and over 250km of tunnels. That is INSANE. It’s like a whole underground city! At its height, there were 800 miners working in the mines and 60 horses! The horses helped to lift cylinders and barrels of rock salt to the surface using a pulley lift system. They were treated very well, but they also spent most, if not all, of their lives underground.

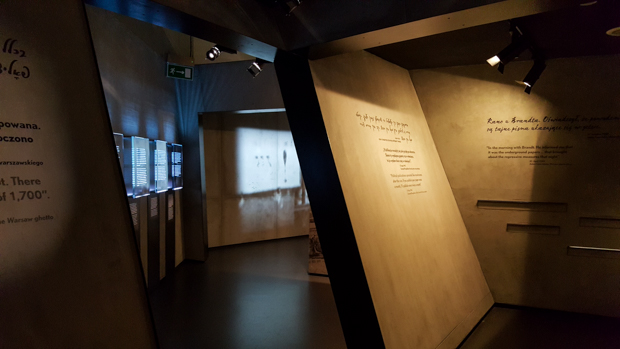

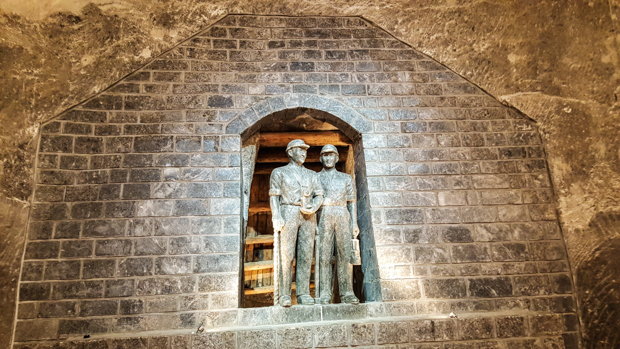

As usual, I did zero research before showing up. I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting, but it certainly wasn’t the underground salt sculpture garden that I got. This mine, at least along the “Tourist Route” (that’s the tour I picked… there are others where you can crawl around less travelled routes, but I wanted to see the highlights. We visited less than 1% of the mine!), is decorated with crazy awesome sculptures, the older of which were carved by miners and the newer by various sculptors.

Well, first you have to walk down a mine shaft via 380ish stairs to where the tour starts, 60 meters underground. Then, you go on a trek through tunnels and chambers and down more and more stairs until your head starts to spin. No wonder you have to go through with a guide! The chambers along the route are named for various famous Poles, including Copernicus, King Casimir the Great, Pope John Paul II, and Polish patriot Josef Pilsudski, among others.

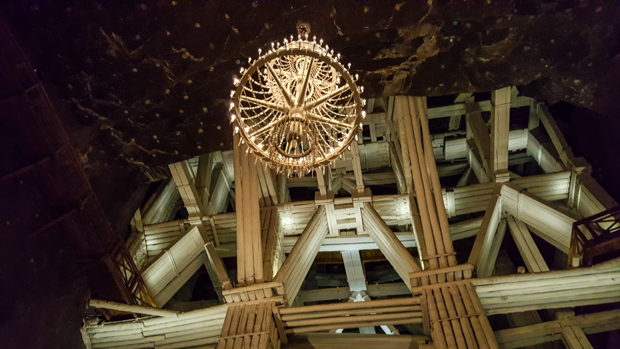

Having my own private tour was literally me living the dream. I asked M every question that popped into my head. Throughout the mines, there are floor tiles made of rock salt, and the chambers and tunnels are lined with wooden supports to prevent cave-ins. I asked M how many trees went into the mines. He didn’t know and also said that I was the first person who ever asked him that question (success!). He explained that the wood is strengthened by the salt which makes it a great option for supports.

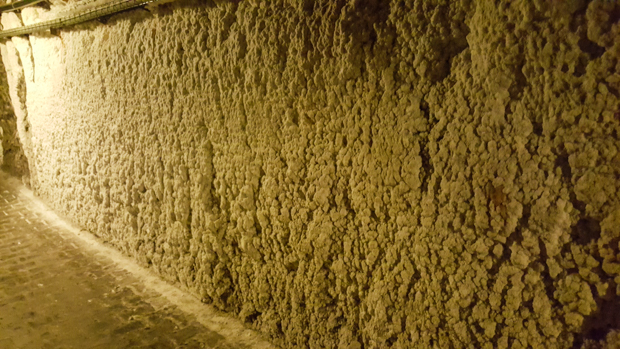

Sometimes, there are salt buildups called cauliflower salt that come from leaks in the mine. When those drips aren’t there, though, it’s easy to forget that you’re literally surrounded by salt. M kept telling me to lick one of the walls because they taste like salt, and I refused because that seems like one of those things guides say so they can laugh while you do something ridiculous. He insisted that it wouldn’t be weird and people do it all the time, but I held out… at least until the end after we parted ways and I had some privacy. The verdict? The wall tasted like salt. True or not, I still think the guides must laugh watching people lick the walls.

One of the other underground lakes has a music and light show. Guess whose music they play? That’s right, Chopin! Who else? I admit that it was kind of awesome listening to Chopin in a huge underground chamber. You feel like you’re physically wrapped up in the music because of the acoustics.

The most epic room along the route is St. Kinga’s Chapel. M told the story of Princess Kinga, a Hungarian princess who married the Prince of Kraków. For her wedding present, she asked her father for salt to take with her to Poland (because salt was so valuable it was even called white gold!). They went to a salt mine in Hungary, and she threw her engagement ring in. It was carried (magically, I suppose) through the salt deposits and when she arrived in Poland, she instructed miners to dig. Her ring was in the middle of the first piece of salt found.

Don’t quote me on that story because there’s a 90% chance I got it wrong. When he first started telling it, I definitely thought it was a real story until it got magically weird and I was just confused… so maybe I did get it right because my retelling is certainly baffling as well.

ANYWAY, the cathedral was the most awesome part of the tour which feels like a cliché because that’s the thing they boast about, but it really is spectacular. There are rock salt sculptures everywhere. It took three self-taught miner-sculptors 70 years to finish. Unreal. It’s also super cool how they use the different qualities of rock salt for different effects. The purer stuff is used when they want it to be more transparent, for example in the light fixtures. The majority of the sculptures are less pure. Everything is carved from Wieliczka salt, with the exception of the nativity scene’s baby Jesus who was carved from special pink rock salt brought from another mine.

The tour took about two hours, but it felt like it was over in a flash. M and I parted ways in this incredibly tall chamber (36m tall!) where he said they once flew a hot air balloon and someone bungee jumped (not simultaneously, I assume). I asked if he’d bungee jump in there, and he said not a chance. I’m with him. It was sad saying goodbye because we were basically best friends after our time traipsing through an underground wonderland together. Though I guess a real friend would know his name.

I was on my own to explore the last couple rooms on the route (this is when I licked the wall) before making my way to the exit. I had to wait for a few more people to accumulate and then I was lifted 135 meters to the surface in a tiny, terrifying elevator with a group of Italians who, based on my limited Italian skills, thought it was similarly terrifying.

Back on the surface, it was raining. Ugh. Of course. I found my way to the bus stop (with only like 10 minutes of wandering around like a lost sheep), rode back to Kraków, and walked home to the hostel. The girl working at the desk just about made my day when she told me there was still food left from dinner. I stuffed my face with a burger and potatoes, took a quick shower, and collapsed into bed. Packing could wait until morning.